Of Arizona bars, and why we won't make them...

We are no longer building saddle trees, but we have two videos about how Western saddles fit horses available on our westernsaddlefit.com website.

There are very few things we won't build when it comes to saddle trees. Sometimes there is a learning curve for things that we haven't built before or different disciplines we aren't very familiar with, but if a customer is willing to work with us to help us understand how they want something built, we will do all we can to make it the way they want. Except... we won't build something that we feel will negatively affect the fit or function for the horse - and Arizona bars fall into that category. We never have, and never will, build an Arizona bar. Here's why...

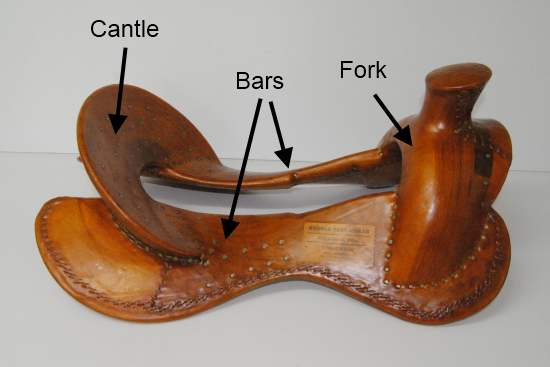

First, lets get some definitions straight. Very basic to start with - the bars are the pieces of the tree that go down the horse's back on each side of the spine. I know some people call different fits by "bars", ie. QH bars, Arab bars, but that is supposed to describe how the bars fit, not what they are. (I realize this is more than elementary to saddle makers, but I have seen discussions on horse forums about what the "bars" really are. Since there is a range of knowledge in the people who contact us after reading our website, I thought I better make it clear at the start.)

There are names that different tree makers have given to the different shapes of bars that they make - Wade bar, Northwest bar, Arizona bar, Arab bar, Mule bar, etc. These names may apply only to the outline pattern of the bar, as for our Wade and "regular" bar patterns. Or they may include the entire spectrum of shapes going into the bar - outline pattern, rock, twist, crown, etc. - which would especially be true for makers who have master patterns copied by duplicating machines.

So while the original Arizona bar would probably have had a specific shape, rock, crown, etc., as the idea was copied and the name was used by different tree makers, these have all changed. The consistent thing with all Arizona bars, however, is the lack of a back stirrup groove.

The stirrup groove is there to make room for the stirrup leather as it comes up, wraps over the bar, goes underneath the bar and out the bottom. Without a groove built into the bottom of the bar, the stirrup leather would make a lump against the horse. Therefore, we always make a full stirrup groove. So why would anyone want to do otherwise?

Well, the back of the stirrup groove is also the narrowest point - and therefore usually the weakest point - on the bar. And this is a very common, if not the most common, spot for trees to break. So someone came up with the idea of not putting in a back stirrup groove in order to make the bar stronger. They named it the Arizona bar. And it became very popular, especially in roping trees which take a lot more stress than basic riding trees and therefore break more commonly.

But this is the result. This is the skirt and the rawhide off the bottom of a tree with Arizona bars which we duplicated due to breakage (ironically at the narrowest point of the bar where the stirrup groove wasn't...). You can see how dark and deep the impression of the back of the stirrup leather is on the skirts (indicating high pressure), and the totally unmarked section behind it where there was no pressure, no real contact with the horse. With this kind of markings on the skirts, you better believe the horse could feel it too.

Here are some pictures of a few trees with Arizona bars which we have been asked to duplicate for different reasons. There are a few different ways these are made - some better, some worse, none we would be happy to build. So when we duplicate a tree, we always put in a full stirrup groove.

On this one, they left a long shallow area and gradually came back up. Basically they decreased the rock in the tree to avoid the lump factor, but...

you can see on the rawhide that, unlike the above picture where the stirrup leather had a lot of pressure on it, the majority of pressure on this tree was carried on the front and back bar pads. However, you can still see the line between where the stirrup leather carried pressure and the no contact zone behind it. This Arizona bar design tries to get rid of the high pressure under the stirrup leather, but results in the pressure being distributed over less surface area than if the whole bar was in even contact. You can see that there is obviously higher pressure fore and aft.

On this tree they actually made more of a groove in the bar with quite a short transition to the back of the bar. This tree has never been built on. (A local saddle maker keeps it on hand to show the differences between a common production tree and one of ours.) But you can imagine that this would result in the same kind of pressure change at the back of the stirrup leather as seen in the previous two examples, and the transition point would still have a high pressure area from the stirrup leather.

I really wish I had pictures of this tree in the rawhide because I don't remember what it looked like. They didn't seem to make any attempt to relieve pressure at the back of the stirrup leather on this one. The wood comes up really quickly and there had to have been quite the lump caused by the stirrup leather. I expect the wear pattern would have been similar to the picture earlier of the skirt and rawhide together.

So basically, the idea of the Arizona bar - no back stirrup groove in order to increase strength - always compromises fit for the horse. Either the stirrup leather protrudes and causes a major pressure point or, by trying to avoid that scenario, the total surface area on the horse is decreased, increasing the pressure on the areas that are in contact. Neither is great for the horse. Yet this is a very common style of bars in production saddles today.

It is easy to tell if there is an Arizona bar in a saddle or not. By lifting the seat jockey, you can see the bar as it goes over the stirrup leather, and if you put your fingers between the bottom of the bar and the stirrup leather you can feel for that back stirrup groove. If it's there, you'll feel it.

Whether Arizona bars actually cause major issues or not depends on the conformation of the horse. Essentially, the stirrup leather protruding below the bar increases the rock in the tree. For horses with lots of rock in their back, it isn't as bad, because that area may not contact well anyway, depending on the shape of the bar. But for flatter backed horses, that stirrup leather will make a high pressure point that can definitely cause them problems.

Because we use good quality wood and rawhide, we are confident in the strength of our trees. (At this point, we have over 2160 trees out there, some for over 16 years now and many with hard use, and have yet to have one come back broken, though we have heard some good wreck stories.) Since we aren't worried about our bars breaking with normal use, there is no reason to compromise the fit for the horse by building an Arizona bar. So we won't.